Noahs' Arc White Paper

"Tinkering with Numbers, Deciding with Words: Fund Management in a Non-Quantitative Market" -> the first public draft of the Noahs' Arc White Paper.

As promised, we’ve completed a draft of our first White Paper, in which we outline our strategy and the systemic market problems that it flows from. It’s quite a dense read, and certainly on the longer end of our content, so no pressure to read the full thing - we’ve designed this to be the most technical and thorough document that we release. It’s soooo long, in fact, that gmail (if you use that) won’t display the full thing in your browser… click through to Substack if you make it that far and want to look the rest over!

We’re hoping that this will articulate all of our thoughts and quell many questions. Of course, we’re always always always open to chat about this or any of the information we’ve released.

The working title is, “Tinkering with Numbers, Deciding with Words: Fund Management in a Non-Quantitative Market.”

After we receive some feedback, we’ll refine it into a final document.

Let us know what you think!

-Noah & Noah

No aspect of this material is intended to provide, or should be construed as providing, any investment, tax or other financial related advice of any kind. You should not consider any content herein or any subsequent services provided to be a substitute for professional financial advice. If you choose to engage in transactions based on the content herein, then such decision and transactions and any consequences flowing therefrom are your sole responsibility. Noahs’ Arc does not provide tailored investment advice to any person directly, indirectly, implicitly, or in any manner whatsoever.

Abstract

Current responses to volatility in the markets are insufficient, over emphasizing short term noise and under emphasizing tail risk. Building off of the work of a number of market practitioners, we attempt to account for these discrepancies by proposing a strategy that utilizes the cash flow from harvesting short term volatility (via the short sale of collateralized options) to implement a tail hedging protocol.

Contents

Introduction

The Problem

Our Solution

Credit Where Credit is Due

Part I: Qualitative Valuations

Problem: Unmoving Quantitative Assumptions

Problem: Too Much Data, Too Much Noise

Solution: Qualitative Arbitrage

Part II: Converting Noise into Opportunities

Stock Prices and Noise

Temporal Bias, Short Term Thinking

Harvesting Volatility

Options and Time Decay

Cash Secured Puts

Covered Calls

Why Not Just Buy the Stock?

No Guarantee of Consistent Returns

Part III: Acceptance of Downside

Modern Portfolio Theory

Value at Risk and Expected Shortfall

Acceptance of Risk + Limited Use of Models

Part IV: Convex Hedging

The Problem with the Long Short Model

Where it Goes Wrong

Correlation vs Causation

Establishing a Causal Link

Convex Payoffs

Our Strategy, Summarized

Conclusion

Influences

Introduction

US Markets are prone to extreme events that represent large scale failures of risk management protocols; most recently, the week of January 25th, 2021 was an extreme crisis for many Long/Short funds as the short squeeze of GameStop (NYSE: GME) and other equities revealed a massive exposure to tail risk in their strategies, namely the uncovered short positions thought by some to provide an adequate protection against risk; the very tactic used to mitigate danger to the portfolio inadvertently created new harm.

This, however, was not the first time that fund killing vulnerabilities were exposed: during 2008, many hedge funds suffered as their long short pairs on convertible notes and equities destroyed their portfolios. This may represent a few extreme examples, but we contend that similar exposure exists all throughout the market, hidden with pseudo scientific risk management tools and investing strategies.

If even the largest and most sophisticated investors are liable to fall, what recourse, then, is left for market participants looking to temper downside?

Oftentimes, the simpler answers are the most sufficient.

The Problem

Much of modern finance is plagued by a number of portfolio killing problems, many of which can be traced back to an over emphasis on faulty quantitative metrics. While statistical analysis can be useful, relying on it too much can result in vulnerable strategies, misallocation of capital, and catastrophic losses. .

Our Solution

First, we discuss how investors can cut through noise by considering simple, qualitative reasoning in their investment decisions; this “qualitative arbitrage,” or analysis of qualitative info that software and quantitative models are unable to touch, is an attractive way to gain an edge in an era of passive investing and quant-trading. Second, we propose the use of option-credit strategies that allow investors to redefine “wins” and “losses” for them and their portfolios by capitalizing on the choppy, short term variance that plagues many market watchers. Finally, we discuss the underestimation of the degree to which tail risk presents a threat as well as a low cost solution to help mitigate this risk.

Credit Where Credit is Due

While we have articulated and presented these ideas, we are truly only curators: we owe a great deal to the thinkers whose thoughts this paper is based on - after our conclusion, we’ve provided a list of some of the major works that we’ve derived our beliefs from.

Part 1: Qualitative Valuations

“I call the flip side to the Wisdom of Crowds the Lunacy of Lemmings,” Ed Thorpe

In our era of big data and easily obtainable information, investors are increasingly relying on quantitative modeling and analysis to get an edge in the market. These once valuable advantages are being eroded by their quantity, availability of data, and a certain cognitive dissonance about what the underlying numbers actually mean. Moreover, while they may work for those highly proficient in math, it is an area with increased competition, making it even more difficult to find success. Given our skill set and knowledge base, we prefer analysis grounded in simplicity and straightforwardness.

Problem: Unmoving Quantitative Assumptions

“It is better to be vaguely right than exactly wrong.” - Caveth Read

Much of finance has a heavy reliance on the Discounted Cash Flow Model, commonly referred to in shorthand as the “DCF.” Our personal theory on a contributing factor to this problem is a “2+2” talent program on Wall Street that generally requires budding portfolio managers to do 2 years in investment banking, followed by 2 years in private equity or in an MBA program before they join a Hedge Fund. As a result, the DCF making bankers find their way on to Wall Street with what will become a dangerous tool. While these DCF’s may function well in the context of private markets for investment bankers, our belief is that, in liquid markets, DCF’s are poor valuation tools; much of the time, they merely provide false confidence.

One of the basic problems of the DCF is that inputs consist of, at best, a number of stagnant, impossible to accurately gauge assumptions, including growth rates of sales and costs. Of course, the creator of the DCF will temper his or her assumptions with a “Discount Rate,” meant to represent the uncertainty involved in the model. Even with this, a few small changes in the model can dramatically alter the result; the magnitude of the changes needed to sink a model are small enough to be attributable to mere statistical noise.

Using this tool to value public equities gives the appearance of a high level of quantitative analysis, but, unfortunately, is often nowhere near as complex or efficient as the math seen at a Citadel or Renaissance.

Still, this “math” gives the creator of the DCF or similar model a sort of armor: one can say, “The numbers couldn’t have predicted this,” rather than, “I was wrong.” The blame is apparently outsourced to a model somehow removed from the realm of criticism rather than to the individual, or team of individuals, that created the model.

One last note is that many proponents of the DCF claim that these tools are “better than nothing.” We disagree - better and more honest, to be straightforward about your own level of uncertainty than to recourse to a model that amounts to the sum of your intuitions but often carries the benefit of greatly increasing confidence without greatly increasing results.

Problem: Too Much Data, Too Much Noise

“Information, in the technical sense, is surprise value, measured as the inverse of expected probability” - Richard Dawkins

Beyond DCF’s, many funds rely on third party data to get an indication of how an investment proposition is doing; data that they believe they can leverage to project changes in stock price. Some classic examples are the number of cars in Walmart parking lots, activity at a factory, and air traffic numbers. While these data points are certainly interesting, it is impossible to prove their true level of efficacy in predicting stock prices. Moreover, they are also now cheap and widely available. So, even if you believe that these numbers were once enough to give an edge, they are now much more likely to be priced in.

Besides that, there is a certain level of variance to be expected in any complex system. The more you obsess over each and every obscure data point, the more likely you are to conflate this natural variance (noise) with real, important information that will have tangible effects on the market or the security in question.

Solution: Qualitative Arbitrage

“Any observed statistic will tend to collapse once pressure is placed on it for control purposes. - Charles Goodhart”

We believe what edge is left in the market is in the analysis of qualitative info. While a lot of qualitative data can be converted into quantitative data, it's the extra info that comes with each data point, the things that cannot be standardized into a spreadsheet, that gives this data power. Data that people cannot come to agreement on the impact of it is data that cannot be properly “priced” into the market. Therefore, qualitative data is a possible place to look for an edge in a quantitative/big data age. We consider a look at and utilization of information that does not easily fit into a model as “Qualitative Arbitrage.”

(To be clear, we are not detracting from the efficiency of hyper quantitative funds - the performance of many of these firms speaks for themselves. However, we believe that there is a strange middleground in which information is not being evaluated properly or qualitatively enough to truly be effective; it is a middle child between simple, heuristic driven thinking and rigorous mathematical trading. This is the area which we seek to operate in.)

Taking any measurement as an indicator of something else is necessarily assuming a strong, consistent correlation, and sometimes even causation (in Part III, we discuss the trouble of relying on correlations in depth). In other words, if we solely measure a company’s Price to Earnings ratio as a metric for investment, we are assuming that a P/E ratio in a desirable range is indicative of outsized returns in the future. While there may be environments in which this is true, we contend, as any rational person would, that it cannot be a consistently successful heuristic. As Goodhart’s Law, quoted above, but more commonly phrased as, “Once a measurement becomes the goal, it ceases to become a useful measurement.”

It is often difficult to maintain a 2 Dimensional measurement of performance. P/E, Price to Book, CAGR of Revenue, or any other simple metric can fall victim to this. If companies were to start optimizing for any single one of these variables, it would very likely be at the expense of other variables that could be equally or more important. Likewise, if fund managers optimize only for these metrics, it can be at the expense of a more holistic picture.

More complex, multi factor filters, incorporating a few of these metrics may be a step in the right direction for solving this issue, but they still may fail to see tangible, important truths that can affect the long term health of a company. So, while we do holistically look at the financial health of a company as told by numerical metrics, we do not overly rely on any one measurement or crutch solely on a suite of possible factors. We take these numbers as far as they reflect reality and then marry them with a literal, tangible understanding of what a company does. We believe this is a better option than expending resources coming to a very specific, but ultimately inaccurate conclusion.

Part II: Converting Noise into Opportunities

“...it is a tale… full of sound and fury, Signifying nothing.” -Shakespeare

Just like an overabundance of data points about a stock can simply be white noise, the price movement in any given security can also simply be meaningless, short term variance. We do not claim to be experts at telling the difference; rather, we employ the simple heuristic that given shorter and shorter time frames over which movements are observed, a higher and higher proportion of that movement tends to be caused by day to day randomness. Armed with this belief, we optimize for converting this noise into capital by utilizing the short sale of options, always fully collateralized with liquidity or equity in our portfolio.

Stock Prices and Noise

*Section updated on Jan 20th*

A useful (non original) frame for looking at the changes in a stock’s price is that, at any given time, the change in a stock’s price is composed of two components: drift (signal) and noise. While drift is a portion of the movement represented by market participants trending towards discovery of a “fair value,” noise is simply random variance in the stock price.

Price Change = Noise + Drift

We cannot say what percentage of any process is noise and what percentage is signal. However, as shown by Taleb, given any ratio of noise and signal over a period of time (such as 1 year), when you take subsections of that period of time (such as monthly periods), you increase the ratio of noise to signal non linearly. The example given by him is that when taking a portfolio with a 15% return in excess of the interest free rate and 10% volatility and viewing it every one year, the ratio of noise to signal should be around .7. Viewed every one hour, however, the ratio becomes around 30 parts noise to one part signal. The full discussion can be viewed in Chapter Three of his book Fooled by Randomness.

To restate the idea once more, a single day will be loaded with a higher proportion of meaningless variance in stock price than a month or year will. We do not intend to use this as an excuse to justify sitting idly by. Rather, we take it as an opportunity to use the meaningless volatility of markets in the short term and become a beneficiary of it, rather than a victim.

Temporal Bias, Short Term Thinking

“Immediacy is a tyrant,” Mark Spitznagel

Beyond the mathematical truth of greater proportions of volatility over smaller time periods, we also hold the conviction that there tends to be a bias away from truly long term thinking in general.

With many investors optimizing for a short term time frame, an earnings conference-call that yields lower profits than expected (for example) is rarely acceptable. However, a more nuanced examination may reveal the sort of news that would make us even more excited to earn the company in the long term: if management is reducing profits by actively reinvesting into the future of the business, then this could very well be a positive long term indicator.

This concept is discussed by Brinton Johns and Brad Slingerlend in their paper on Complexity Investing, and a similar sentiment is expressed in Mark Spitznagel’s terrific book, The Dao of Capital: Austrian Investing in a Distorted World.

Harvesting Volatility

Given the heightened volatility that exists in the short term, we believe that there are two rational responses: pick the sort of investments with which you can feel confident ignoring the noise, or, alternatively, take advantage of the volatility. We have elected to pursue both of these options.

In regards to the former, we have already given some indication to the fact that we look to invest in sound, rigorous, and robust businesses (as discussed in Part III and IV, though, we temper this belief with downside protection). In regards to the latter, we turn to options for a solution.

Options pricing is complicated and nuanced. A large portion of the pricing is related to the market’s expectation of movement in the stock price, or Implied Volatility. For this reason, options pricing can be viewed as a reflection of the market’s uncertainty in regards to a future price of a stock. There are techniques with which you can actually estimate an implied movement in an underlying stock price based on the price of the options.

The higher the market’s uncertainty in regards to the underlying stock, the higher the options price will tend to be. So, by electing to sell options, we are taking advantage of this volatility. In a way, we are saying that we are willing to assume the risk of the price movement in exchange for cash.

This may seem counterintuitive, given our risk aversion. However, as explained below, the risk we are assuming is not substantially different from out right equity ownership and, moreover, we match the position with a hedge for the worst case scenario.

Below, we articulate what exactly our short sale of options involves; before we do so, however, we include a brief note on options and time decay.

Options and Time Decay

An interesting and easily observable trend is for the pricing of options to scale non linearly with time. In other words, an option expiring in one month will not be only half the price of an option expiring in two months; rather, it will tend to be more. The graph below illustrates this relationship.

Given this, all things held equal, selling an option at the start of month one expiring at the end of month one and then proceeding to sell an option at the start of month two expiring at the end of month two will yield more than selling an option at the start of month one expiring at the end of month two.

In short, when one is selling options, it is often beneficial to look to the shortest time frame over which one can sell the option; repeating this process over and over again may very well yield more than selling one longer dated option. (Due to liquidity, this paradigm may change if selling further out of the money, but our strategy does not deal with this.)

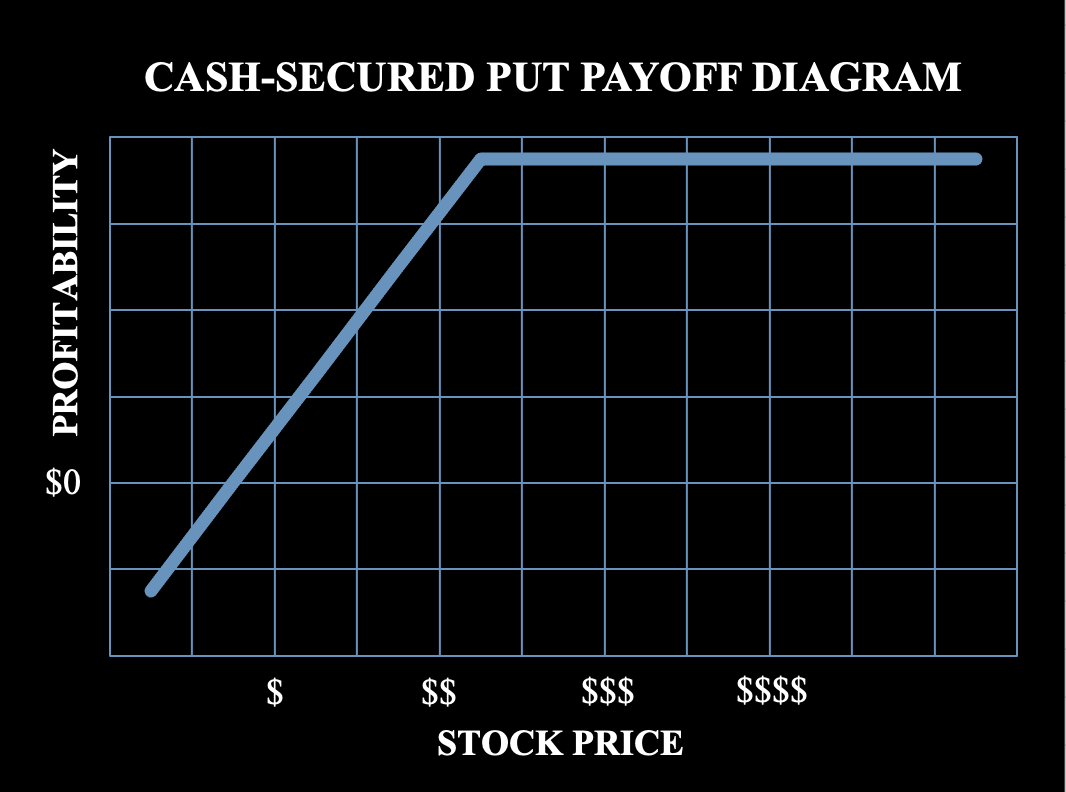

Cash Secured Puts

Selling 1 put contract is the sale of the promise to buy 100 shares of an underlying stock at the predetermined strike price (the place where the contract executes). As an example, if stock A is trading at $20 a share, you can potentially sell a put contract with a 19 strike in exchange for $.30 a share. In this instance, your account would receive $30 ($.30 x 100) in credit.

Additionally, you would now be obligated, in the event that the counterparty exercised your put option, to purchase 100 shares of stock A at $19 a share, regardless of what the stock price is. This would cost $1900 ($19 x 100), regardless of whether or not the stock descended to $18.99 a share or $10 a share. This can result in the immediate accumulation of an unrealized loss in adverse market conditions.

Whenever we sell a put, we ensure that we have the liquidity to buy the shares with cash in the event we are exercised; we never rely on margin.

Covered Calls

A covered call functions as a promise to sell your shares in the future for a fixed price (the strike price) in exchange for a payment up front today. For example, let's say stock A (mentioned before) falls below $19. At this point (because of the put we sold), we would own the stock at a cost basis of $19.

From here, we would now sell covered calls against the shares, collecting extra income. In the event the stock dropped to $18 a share, we may be able to earn another $.25 per share on the sale of the covered call option at a strike of $19 a share. On 100 shares, our account would be credited with $25 ($.25 x 100). In the event the stock price exceeded $19 a share, we would be asked to sell our 100 shares at $19 a share, regardless of how high the stock appreciated. While we cap our gains in the event stock prices rise, we generate consistent income.

Why Not Just Buy the Stock?

By selling puts and calls rather than simply opening long positions in the stocks we favor, we are able to transform market noise and variance into capital. If, over the same two week period as given in the example, we had purchased 100 shares, and did not buy or sell in response to market moves, our effective return would be 0%, as we followed the price per share from $20 down to $18.50 and back up to $20. Instead, we were able to return $.55 per share over the same time frame ($0.3 from selling the cash secured put, $0.25 from selling the covered call once we owned shares).

We cannot emphasize enough, however, that this is a very idealized example of our strategy at work, one in which we are able to reliably collect high premiums over two consecutive weeks. There are weeks, months, or longer, in which these sorts of premiums cannot be expected to be collected in the event that the stock price is too low. However, in this scenario, normal shareholders of the equity would also have no recourse to mitigate their losses.

Take the below alternative price chart as an example: after we sold the 19 strike put and the 19 strike call, the stock could have dropped to $13 a share. Assuming that this is isolated to the individual equity, we will be stuck in a position that will generate little, or, more than likely, no yield at our cost basis of $19 a share.

However, if this is a sector or market wide downturn, we prepare for this sort of situation with the tail hedging protocol developed and discussed in Parts III and IV. One of the more adverse market conditions for us may very well be a moderate, 5% to 10% downward drift in our individual equities with no accompanying large scale sector declines or spike in volatility.

No Guarantee of Consistent Returns

We cannot emphasize the fact that this strategy does not in any way guarantee consistent returns reflective of any of the above examples. Again, the stocks can drift down below our cost basis without a necessary spike in volatility; on the other end, they can shoot up in value in a quick enough period of time that we are unable to capture most of the upside.

That being said, we believe that in the mid to long term, our collection of premiums from the short sale of options will provide us with the liquidity to maintain our tail hedging strategy and create returns for the investments in the strategy.

Part III: Acceptance of Downside

Just as we are wary of over relying on quantitative methods in valuing companies, we are also very wary in regards to the use of quantitative methods for risk management.

The use of traditional risk management techniques to estimate the likelihood of downside simply does not adequately indicate anything near to the true amount of risk that investors in equity markets are taking on.

Modern Portfolio Theory

“During a time of crisis, correlations go to 1.” - Market Wisdom

Proponents of the Modern Portfolio Theory may glean the important insight that diversification can be beneficial from their belief; however, an over reliance on the investing system presents a false sense of security.

In essence, Modern Portfolio Theory discusses a trade off between risk and return. If asset A has higher risk than asset B, then the expected return of asset A must be higher than the expected return of asset B to justify an investor purchasing it. Asides from the difficulties in quantifying risk and return, this, in principle, seems very sound - of course, if something is riskier, you should expect to earn more for making an investment in it. A venture capitalist does not intend on returning 10% on a single investment, just like someone purchasing US Treasuries cannot expect to return 10% on a single investment, although for very different reasons.

Still, when dealing with publicly traded companies, we contend that quantified risk is generally understated. Whether it be the probability of another Enron sized fraud or a Kodak sized market shift, companies can go from blue chip to penny stock in a very short period of time. Something like Modern Portfolio Theory can give you the false sense of security that makes you forget that.

The second part of Modern Portfolio Theory becomes even more problematic. The overarching idea is that one can reduce risk by investing in multiple, uncorrelated assets, or even assets with low correlations. Again, while, in principle, this makes sense, when it comes time to begin to quantify the correlations of assets, problems arise. Two equities that may have a correlation of .3 today (meaning that 30% of the movement of one of the stocks is reflected with movement in the other stock) can have a .5 or .7 correlation tomorrow… or, worse yet, their correlation can become 1. As the old adage goes, “during a time of crisis, correlations go to 1.” In other words, when markets are in crisis, all stocks drop and the correlation goes to 1.

If you’re attempting to design a portfolio to survive during a time of crisis, one might ask why you’d rely on a risk management system that’s based off of a variable (correlation) liable to change in a time of crisis. If this seems counter intuitive, it’s because it is.

Again, we don’t disregard the general takeaways from Modern Portfolio Theory… rather, we question it’s technical use in practice. For a more thorough understanding of Modern Portfolio Theory, click here.

Value at Risk and Expected Shortfall

A more institutional tool for risk management is Value at Risk (VaR).

First, VaR assumes a normal distribution of market outcomes. A normal distribution is a probability distribution that not only assumes equal likelihood of positive and negative events, but also bases its estimation of what the distribution looks like based on past market data.

First, the problem with past data - put simply, before the “biggest catastrophe” occurred, you could not possibly predict it by past data alone. If one tried to predict the death toll of the next world war based off of the death toll of WWI, the prediction would not only be useless, but nearly laughable in it’s inaccuracy.

Generally speaking, we favor a lognormal distribution over a normal distribution for individual stock returns; however, for the risk in portfolios, which is what VaR measures, normal distributions are generally used. Regardless, while lognormal distributions may be slightly superior than normal distributions for individual stocks, and normal distributions may be superior for portfolio risk, in the context of the VaR methodology, either would fall short.

The problem comes with the “tail risk,” or the risk associated with the extreme events. In VaR, the risk manager gives an interval that they want to be hedged for - a 99% interval means that they would like to be prepared for the outcome that their distribution claims (or losses) will happen 99% of the time. Asides from the problem of this distribution being based off of past data, it ignores the most extreme events, which are exactly what are in most need of hedging.

As an example, if the cash needed to cover the 99.9% of events being accounted for is $20M, the expected value of the .1% left unaccounted for could be as high as $30M; going based off of the 99.9% estimate could leave you exposed to another $30M worth of losses in the event that the “least likely” event occurs. Again, this is exactly the thing you should be preparing for.

Recently, VaR measurements have been made a bit more strict for banks regulated by Basel II, combining a 97.5% VaR model with an “Expected Shortfall” metric, which is an attempt to take the expected value of the 2.5% worst case scenario event. This may be a step in the right direction.

However, a more compelling step made by the same regulatory body is the outlawing of risk models for divisions in banks for which these models are not accurate. We find this update to be more refreshing and reflective of what we think is appropriate: after-all, even Expected Shortfall can fall short when you cannot truly model tail risk and all you have to go off of is past data.

Acceptance of Risk + Limited Use of Models

“Memento Mori / Remember, you must die,” - Ancient Wisdom

While there are some statistical distributions that may be a slightly more adequate model for market returns, we still do not feel comfortable crutching on these when it comes to estimating the potential extreme downside. Instead, we fully embrace the possibility of a detrimental, disastrous downside as likely enough to account for. That is all that matters - a massive market correction is always a possibility.

Where we do choose to employ models, the consequences of the model’s potential errors do not stand to create a disastrous outcome. An example is when we are deciding whether to sell puts 2% out of the money or 1% out of the money. Here, the worst case scenario has already been addressed with our tail hedging protocol. If the model we incorporate is erroneous, we are not exposing ourselves to a substantially greater downisde than if there were no model to begin with. Rather, it is an exercise in math and probability we employ in an attempt to maximize this portion of the cash flow for the most likely scenarios.

In short, our investment strategy is contingent, first and foremost, on the assumption that we cannot accurately predict the likelihood of a market catastrophe. As a result, we are always incorporating some sort of hedge in our portfolio to offset market downside when it does inevitably occur. We act as if the worst case scenario can, and will happen, at any time. Any theorizing beyond this takes this apocalyptic view as a baseline. Hence, tinkering with numbers, deciding with words.

Part IV: Convex Hedging

Only when the cold season comes is the point brought home that the pine and the cyprus are the last to lose their leaves. - Confucius

Given that we’ve accepted an inevitable downside, the million dollar question becomes how best to prepare for it. We explore the previously mentioned long/short solution and then provide what we believe is a more appropriate method.

The Problem with the Long Short Model

The long short strategy, perhaps now less common than in the past, involves the purchase (or longing) of certain securities while selling (shorting) other securities.

The metrics for determining which stocks are to be longed and short vary from fund to fund, but a simple example is selecting two equities in a sector and purchasing the one the fund manager views as a superior investment and shorting the one the manager views as the inferior investment.

Take car manufacturers A and B. Perhaps a fund manager believes that car manufacturer A is undervalued by the market, while car manufacturer B is overvalued. In a long short fund, this may translate to the purchase of shares in manufacturer A and the sale of shares in manufacturer B.

For the strategy to work, in the event that the car manufacturing sector appreciates in value, Manufacturer A is supposed to gain more in value than Manufacturer B. If that were to happen, the investor would make more on A than they would lose on B. On the other hand, in the event that the sector depreciates in value, Manufacturer B is hypothesized to lose more value than A, thus providing a net payout to the manager.

Where it Goes Wrong

In principle, the long short strategy makes sense. However, there are two problems that make us uncomfortable with the strategy: the stocks may not move in tandem (even if the investor is correct about his/her thesis!) and that there is unlimited risk, a rather unfortunate flaw for a strategy that’s reason for being is to hedge, or mitigate risk.

In regards to the first problem, let’s assume that the investor was correct - A is undervalued. As a matter of fact, it is so undervalued that investors have ignored the massive cash position it has acquired, a position massive enough to perform an acquisition of Manufacturer B, a company so poorly managed that it now has no choice but to take the offer from A.

Then, as is the case with many mergers, the price of Manufacturer A decreases due to the impending loss of cash, while the price of Manufacturer B nears the buyout price of the stock.

Fundamentally, the investor was correct in his analysis - A is a ‘superior’ company to B. However, as we can see, this may translate into the literal opposite of what the investor needs to happen to make money. Here, he loses money on A on its way down and loses money on B on its way up.

This hyper specific example is not the only way the investor loses, though. The stock being shorted can also appreciate in value drastically without having any, or only a nominal, effect on the price of the stock being longed.

As we saw earlier this year, Gamestop and a number of other stocks in early 2021 made outsized, abnormal movements in a short period of time. When the “long/short” pair trade is based on a cross sector thesis, “Long the future (Microsoft), short the past (GameStop)” there is a chance that there is very little short term correlation between the performance of the long and the short stocks. (This, of course, represents another quantitative error that we will discuss briefly - the conflation of correlation with causation.)

This brings us to the second point - there is no limit to the risk that one takes with an uncovered short position. While longing stocks and not utilizing leverage, the risk is limited to the money you put in. If you invest $20, you can only lose $20. On the other hand, when you perform an outright, uncovered short, you introduce the possibility of infinitely high losses. A stock can only go down to 0. It can go up as high as the market will take it; so, if you lose money as the stock appreciates in value, you have uncapped risk.

Even though a $20 stock going to $400 or even higher is a very low probability event, we have already explained that we do not feel comfortable pushing low probability events under the rug. Therefore, this sort of hedging is not only sometimes ineffective in practice, but ultimately introduces steeply unacceptable tail risk.

Of course, some funds make this work with hedges on their hedges and rigorous stop loss protocols; again, we’d group these investors closer to the class of true quantitative players, a classification that is all but needed to be truly secure with this type of strategy.

Correlation vs Causation

A problem that often arises in human reasoning is the conflation of correlation with causation. Grouped together with the sequential bias, this error involves seeing that two things happen simultaneously or shortly one after the other and assuming that one caused the other to happen.

If you Google “Spurious Correlations” you can find thousands of examples of things that correlate with each other but are not caused by each other. We’ll link a website full of these here, but we thought we’d include a few of our favorites:

From 1999 to 2009, Per capita cheese consumption nationally correlates strongly with the number of people who died by becoming strangled in their bed sheets (r = 0.9471).

From 1999 to 2009, Per capita margarine consumption correlated well with the divorce rate in Maine (r = 0.9926).

From 1999 to 2010, People who died by falling out of their bed correlated well with the number of lawyers in Puerto Rico (r = 0.957).

While it may be tempting to try to dream up a reason why these are correlated, we assure you that, beyond a reasonable doubt, these events are random. It's that psychological urge, that human desire to logically explain random phenomena that creates a lot of the danger in modern investment funds. Our modern statistical and mathematical capabilities have led us to try to rationalize the world of randomness.

In other words, it's massively important not to fall into the belief that one of these events occurs because the other did. This rule seems simple, but it is an error that both authors have admittedly fallen into ourselves, and it is an error that we have also seen quite often from many of the career academics at our school. It is massively difficult to escape. Still, it should be avoided at all costs, especially when making financial decisions for an investment fund full of capital from those who put their trust in you.

In the investing world, these biases are all the more insidious - if your favorite stock increases 1% every day on which the Fed meets, you may very well think that the Fed meeting caused your favorite stock to increase in value. However, a 1% variance in your favorite stock’s price may be par for the course… don’t forget the earlier bit on how variance is more common as a percentage of movement in shorter time frames. It is incredibly hard to extrapolate short term movement to a narrative of cause and effect.

We’re not trying to dispel using any statistical analysis from all investing methodologies. From an actuarial perspective, there still may be a systematic betting strategy that works well going based off of certain signals, but it would be hyper erroneous to bet the house on these signals. Many successful betting systems only work because they focus on tempering the percentage of capital allocated. Read about the Kelly Investing Criterion for more on an efficient way to scale bets given uncertainty.

Bringing the concept full circle: just because GameStop and Microsoft tend to move in opposite directions, one does not necessarily move because of the other, and it is massively dangerous to think so. Certainly, it is disastrous to invest your entire fund on this assumption. Moreover, even if an entire fund is not technically bet on one long short pair trade, if the trade can sink the fund, then, in principle, the fund is bet on that trade.

Establishing a Causal Link

Our goal is to establish a degree of causality between the stocks we bet on going up and our hedge used to offset losses when the stocks go down.

Part of our strategy involves selecting 3 or 4 equities in a given sector. One necessary condition for the selection of any of these stocks is their presence or weighting in an exchange traded fund that also houses the other 2 or 3 equities from the sector. So, if we pick stock X, Y, and Z in Sector A, we will find an exchange traded fund tracking Sector A that houses stocks X, Y, and Z. Their composition/weighting in the ETF will generally amount to something in the range of 10% to 20% of the total ETF.

This does not, unfortunately, guarantee that if stocks X, Y, and Z all go bankrupt, the ETF will also go to 0. It does, however, establish that, by the nature of owning shares of X, Y, and Z, that the ETF will have to see sell pressure on it’s price, positively impacting the value of our hedges.

Convex Payoffs

“Heads I win, tails I don’t lose that much.” - Mohnish Pabrai

The problem of introducing inordinate loss potential via a strategy for hedging, as seen in the long short strategy, is one that we intend on turning on it’s head.

Rather than taking positions, such as an uncovered short sale of stock, that may result in marginal gains in exchange for astronomical losses, we seek a position that produces proportionately high returns in exchange for nominal losses.

Given the ETF’s selected above, those that house our chosen equities, we proceed to purchase puts, using the cash flow from the sale of our cash secured puts.

Longing a put presents a convex pay out with limited downside. In other words, our maximum loss is equal to the capital outlay, while the return that we are exposed to scales non linearly. Running the risk of greatly over simplifying the non linear relationship: if one were to short the ETF, and the ETF decreased in value by 20%, the short position would effectively return 20%; on the other hand, if one were to bet against the ETF using put options, a 20% decrease in the value of the ETF can translate into greater than a 20% return on the position, say 100%. (100% is admittedly tame in a steep, 20% decline, but the example is given to temper expectations). Below, we’ve given a graph comparing a potential linear vs nonlinear payoff.

To clarify, this does not mean that the net return on our strategy will be equal to potentially triple percentage option returns; the hedge itself may return at this rate, but the hedge is only part of our portfolio. It exists as an economically efficient way in which to offset potential losses.

This is the beauty of options - they provide leveraged returns without leveraged risk. When we purchase a put, the most we can lose is the capital spent on the put, while what we stand to gain is a multiple of this cost.

Our Strategy, Summarized

The underpinnings of our strategy can be found throughout the paper; we’ll lay it out more formally here.

First, we use qualitative reasoning to select a sector. We are not committed to a rigorous set of metrics at this level, but rather tend towards businesses that are not currently covered by the news cycle and have generally more capital intensive models.

Second, we select 3 or 4 optionable equities in the sector that we believe have relatively tame or fair valuations. Oftentimes, we will find businesses within a sector that have some degree of removal from one another; perhaps they will be located at different points on the supply chain. Additionally, the equities must be found in the same, optionable ETF.

Third, we will sell cash secured puts on the selected equity while purchasing deep out of the money puts on our hedging ETF. While the ETF’s options will be longer dated, the short puts generally expire between a week and a month.

Finally, once the short puts expire, we will either sell more if they expire worthless, or, in the event that we are exercised, we will proceed to sell covered calls on the position at or above our cost basis. All the while, we will be using some of the cash flow to roll the long puts periodically.

When we see fit, we will roll out of a sector, retiring it for the time being, as we open positions in a new one.

Conclusion

For as long as there have been stock markets, there have always been investors betting on companies claiming “I have the winner, I have the stock that will perform best over the next X months.” If we could not see it before, with the wild and crazy ways the market has performed since the outbreak of COVID, we should be able to observe that, quite frankly, these bets and their outcomes have a degree of randomness. Given this degree of randomness, we must redefine the way we “bet” on equities. By employing a credit generating options strategy on stable equities and coupled with solid hedging, investors can potentially enhance stability in their portfolio and help turn the wild west that is stock picking and fund management into a more tame field. While many have tried to create balanced portfolios with complex financial models and sophisticated pricing algorithms, it only takes events like the GameStop short squeeze early in 2021 to remind investors that randomness truly reigns.

To create new opportunities and to subtract many of the current problems of the market, investors need to adopt a mindset focused on new market participation strategies with qualitative, not quantitative investment thinking, and an acceptance and preparation for the inevitable fall.

Influences

We’re both cognizant that we are still quite young, especially for this space. While we’d like to think we’ve had a few dense experiences that have informed our world views, we cannot overemphasize the impact that many books and the great thinkers behind them have had on us. We’ve listed some of the more notable ones below.

Books

The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable, Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Fooled By Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and the Markets, Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Antifragile: Things that Gain from Disorder, Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Meditations, Marcus Aurelius

Science Fictions: How Fraud, Bias, Negligence, and Hype Undermine the Search for Truth, Stuart J. Ritchie

The Dao of Capital: Austrian Investing in a Distorted World, Mark Spitznagel

Complexity Investing, Brinton Johns and Brad Slingerlend

The Most Important Thing: Uncommon Sense for the Thoughtful Investor, Howard Marks

The Analects, Confucius

The Selfish Gene, Richard Dawkins

A Man for All Markets, Edward O. Thorp

Talking to Strangers, Malcolm Gladwell

The Hour Between Dog and Wolf, John Coates

Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell

Apocalypse Never, Michael Shellenberger

Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future, Blake Masters and Peter Thiel

Hedge Funds, Humbled, Trevor Ganshaw

Wow, that’s a lengthy document… if you’ve made it this far, we hope you found it helpful. We’d love your feedback to refine and improve what we’ve laid out here!

Stay warm.

Best,

Noah & Noah

DISCLAIMER

> The information and opinions contained in this newsletter are for background purposes only and do not purport to be full or complete. The information herein is not personalized investment advice or an investment recommendation on the part of Noahs’ Arc. No representation, warranty, or undertaking, express or implied, is given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information or opinions contained herein, and no liability is accepted as to the accuracy or completeness of any such information or opinions.

> All investments involve the risk of a loss of capital. Noahs’ Arc believes that its proprietary investment program and research and risk-management techniques moderate this risk through the careful selection of portfolio investments. However, no guarantee or representation is made that our investment program will be successful, and investment results may vary substantially over time.

> Certain information contained in this document constitute “forward- looking statements,” which can be identified by the use of certain terminology, such as “may,” “will,” “should,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “project,” “estimate,” “intend,” “continue” or “believe” or the negatives thereof, or other variations thereon or comparable terminology. Any projections or other estimates in this document, including estimates of returns or performance, are “forward- looking statements” and are based upon certain assumptions that may change. Due to various risks and uncertainties, actual events or results, or the actual performance of any investment vehicle, portfolio or product described herein may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in the forward-looking statements. Actual events are difficult to project and often depend upon factors that are beyond the control of Noahs’ Arc.